Nature is Infrastructure. Why Are We Failing to Fund It?

We treat nature like a charity instead of a critical utility—here's how we build a new financial model.

Carbon Credits

Company News

Nov 10, 2025

Siya Kulkarni

infrastructure (n.): the basic physical and organisational structures and facilities (e.g., buildings, roads, and power supplies) needed for the operation of a society or enterprise

Human civilisations have relied on nature for as long as they have existed. From the Indigenous cultivators of Terra Preta (dark earth) in the Amazon, to the great societies that flourished along the Nile, Indus, and Yellow Rivers, to the multi-billion-dollar ecotourism industry sustaining modern economies, nature has always underpinned human progress. It has regulated, protected, and provided for us in countless ways.

Nature is infrastructure too – yet restoration and conservation initiatives remain systematically undervalued and underfunded. According to Nature4Climate, private finance flows that negatively impact nature amount to roughly US$5 trillion per year, about 140 times the value of private investments in nature. This imbalance is striking, especially when biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation are estimated to place US$25 trillion of global economic output at risk annually.

Traditional infrastructure projects (think power plants, roads, dams) are defined by predictable cash flows, long-term contracts, and government guarantees. Nature-based projects, by contrast, are often perceived as riskier: their revenue models are less certain, their benefits diffuse, and their performance more difficult to quantify. Our financial systems have been designed to work with engineering certainty, but struggle to accommodate the natural variability, where success depends on the resilience and response of living ecosystems.

Building the Scaffolding for a New Asset Class

Yet roads, dams, and power grids did not begin life as risk-free propositions either. They became viable through public guarantees, co-investment, and a broad societal consensus that such assets serve the common good. If we begin to view natural systems — from mangroves to reforestation to coral restoration — as resilience infrastructure that both generates returns and prevents economic and social losses, we can start building the same scaffolding around them: financial frameworks, policy incentives, and community support that treat nature not as a charitable cause, but as a critical public utility for the 21st century.

The Great Misalignment: Ambition vs. Accessibility

Despite the growing enthusiasm for nature restoration, many projects find themselves caught in a widening gap between ambition and accessibility. The barriers are borne out of a huge misalignment of goals – a system designed for speed, scale, and certainty struggling to accommodate the complexity and patience that nature requires. In practice, this has created a quiet power imbalance between those who hold the capital and those closest to the ground. Investors and buyers often set thresholds so high, such as demanding proven track records, strong credit ratings, or double-digit returns, that smaller, early-stage projects are effectively excluded from consideration. The result: capital sits on the sidelines while credible, high-impact projects fail to launch.

Even when interest is there, the process itself can become a barrier. Due diligence timelines can stretch over months, sometimes years, consuming scarce resources and momentum. For nature degradation and climate change, which don’t wait for approvals or funding cycles, this pace can be fatal. At the same time, opaque contracting practices add further strain. Developers often face little clarity around pricing structures, liability clauses, or what constitutes financial strength in the eyes of buyers. Integrity and accountability from the developer are vital, but without clear, consistent standards, the due diligence process can feel opaque, transforming a safeguard into a source of frustration.

To add fuel to the fire, developers and communities too often see few benefits of the capital pledged in their name. In some cases, the contracts they secure transfer nearly all delivery risk downstream. A delayed verification, growing climate risk, or a shift in methodology can trigger hidden economic and timing penalties that could push small developers to the brink.

A New Toolkit for a New Infrastructure

The path to scaling natural infrastructure lies in collaboration, not exclusion. Early engagement between investors, buyers, and project developers is critical – from co-designing feasibility studies, to agreeing on verification frameworks that measure ecological outcomes fairly. Shared investment in baseline data and advanced monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) ensures all parties have confidence in a project’s performance and long-term viability. Standardised, transparent offtake templates with balanced risk allocation can further reduce friction, making contracts both fair and actionable.

Investors and buyers do not need to lower their standards. Rather, rethinking how they engage could turn today’s bottlenecks into tomorrow’s bankable projects. Just as traditional infrastructure relies on partnerships and shared ownership to succeed, nature-based projects require trust, long-term collaboration, and aligned incentives. If we approach restoration and conservation as co-developed public utilities, we can transform high-barrier projects into accessible, investable opportunities.

Several tools already exist to bridge the gap between ambition and investability. Blended finance and catalytic capital can absorb early-stage risk, helping projects reach the threshold where private investors can participate. Outcome-based payments, tied to verified ecosystem performance, ensure that financing rewards real impact rather than symbolic pledges. Portfolio approaches allow investors to diversify risk across multiple projects, reducing exposure to individual uncertainties. Transparent standards for project eligibility and developer qualifications further create predictability for all parties involved.

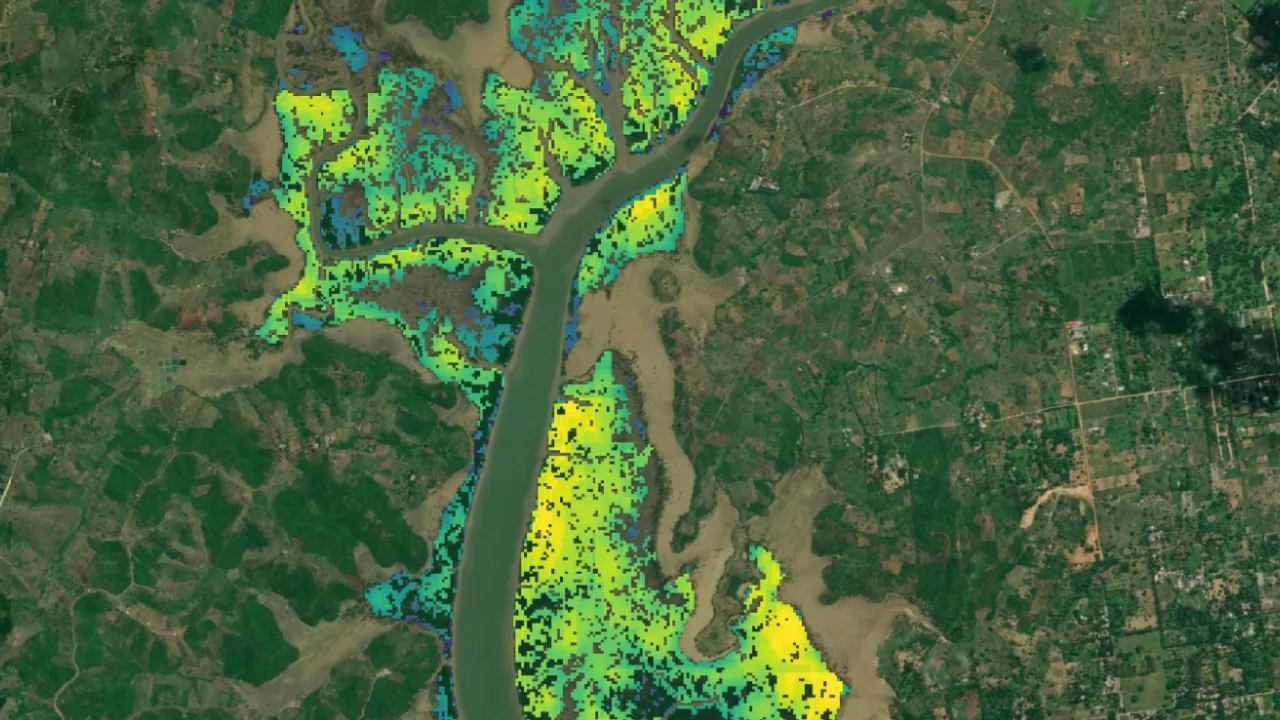

On the physical side of implementation, digital MRV tools – now capable of detecting individual trees and tracking ecosystem change in near real-time – can strengthen confidence in reported outcomes. By improving data accuracy and transparency, these technologies can help unlock outcome-based payments and reduce uncertainty around a project’s true impact.

An Investment in What We Can Grow

Ultimately, the maturity of natural finance will depend not solely on new capital, but on new behaviours: more transparency, greater patience, and deeper partnerships between governments, investors, and local implementers. By embracing shared responsibility and fair engagement, the sector can unlock a broader pipeline of credible, high-impact natural infrastructure projects.

Nature is infrastructure – foundational, enduring, and essential. The progress we’ve seen in private and public investment, policy frameworks, and standards is encouraging, but the pace remains insufficient. The capital exists, the science is clear, the need is urgent – and the tools and technology to support this are also progressing. What is missing is alignment between ambition and accessibility, rhetoric and reality.

To build the resilient economies of the future, we must invest not only in what we can pour concrete over, but in what we can grow, restore, and sustain together. By treating natural systems as the living infrastructure they truly are, we have the opportunity to safeguard livelihoods, protect ecosystems, and create returns that last for generations.