Navigating the Biomass Model Landscape: A Constructive Comparison

We compared leading commercial models against our biomass models engine to investigate why carbon estimates diverge and how to avoid the costly risks of "phantom biomass."

Company News

Science & Tech

Project Development

Carbon Credits

Jan 15, 2026

Matt Amos

The carbon market is evolving rapidly. We are now seeing a proliferation of models and products designed to quantify above-ground biomass across the globe. But before diving into the comparisons, it is worth clarifying what these tools actually do. To a project developer, a biomass model is the translation layer between raw satellite data and a carbon credit. It takes signals from space (like radar or optical imagery) and converts them into an estimate of physical biomass on the ground. Modelling remotely saves the time and expense of performing project censuses on the ground.

For a project developer, this model is your bank balance. If the model overestimates, you risk issuance reversals. If it underestimates, you leave revenue on the table. Choosing the right one isn't just a technical exercise—it’s a commercial necessity.

Not All Models Are Created Equal

Much like climate models, every biomass model is built differently. They use different design architectures and training data. Consequently, they perform differently depending on where you look. One model might be the gold standard in the tropics, while another offers greater certainty in boreal eco-regions.

In the climate world, we rely on massive comparison projects like CMIP6 to make sense of these differences. These experiments let us compare outputs side-by-side to understand performance and build consensus. While the biomass community might not need a project of that sheer magnitude right now, the principle remains. We can all benefit from peeling back the hood and investigating why our results differ.

Why? Because these models are beginning to underpin the Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM). Standards and methodologies are moving toward data-driven outputs to back up sequestration claims and set baselines. But with standards bodies often under-resourced, and technology moving at breakneck speed, it can be a minefield for project developers to know which data to trust.

At Treeconomy, we decided to run a mini-comparison of our own. We investigated various paid products alongside our own upcoming free models on a site we know well. The goal here isn't to critique named providers or models. It is to start a constructive discussion about strengths, weaknesses, and applicability of biomass models generally to help the market mature.

The Setup

We collected data from a variety of commercial providers (accessed via API or data request) and included two early versions of Treeconomy’s own biomass models.

To make this fair, we standardised everything:

- Grid: All data was re-gridded to a common geospatial resolution and projection

- Time: We aligned the temporal resolution to be annual.

- Units: All data was converted to above-ground biomass density (AGBD) in megagrams per hectare (Mg/ha).

- Location: We looked at the Knepp Estate in the UK. This is a classic rewilding project that falls within the standard GEDI satellite operating latitude, meaning there should be a good density of space-borne data available.

Note: While some products go back 20+ years, we focused on the years where all products overlapped, specifically looking at the range 2021 to 2024 inclusive.

Spatial Resolution and The "Zero" Problem

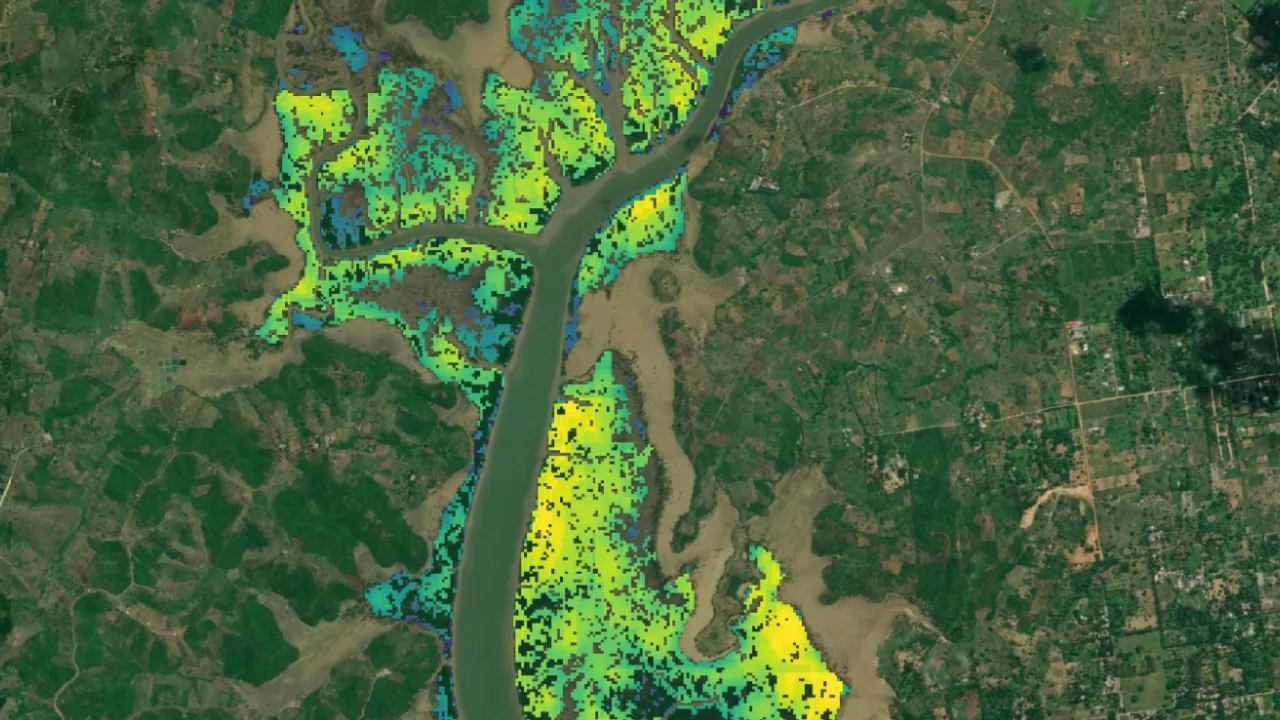

For non-geospatial experts, the most intuitive place to start is looking at the maps.

One of the starkest differences we found was the ability, or inability, of models to estimate zero biomass. In the data from "Provider A" and "Provider F", we saw large areas that we know are recently arable fields (empty of trees) being assigned non-zero biomass values.

Why does this happen? It likely stems from the uncertainty in the underlying satellite data, like GEDI, combined with the fact that biomass data is what we call ‘zero-bounded’—meaning you cannot have negative biomass. This makes traditional model training tricky, and many models struggle to predict zero effectively. If a model relies purely on regression without a "classification step" (a check to see if vegetation is actually present), it might smooth out the data. This could assign a value of, say, 20 tonnes per hectare to a bare field.

Why this matters for the market: This is a major issue for baselining. If you are developing a project on an empty field, but the model thinks there is already 20t/ha of biomass there, you are effectively starting your project in debt.

You have to grow 20 tonnes of real trees just to get back to the model’s 'zero' baseline before you can claim a single credit. Models that fail to classify zero correctly challenge project viability, especially for ARR projects.

Conversely, models that include a forest classification step (Providers C and D in our analysis) showed a sharp spike at zero, correctly identifying empty space.

In the following plot, we look at the distribution of biomass density values across the different products. This backs up our earlier assumption that there are two models here which are especially good at predicting zero where there is no biomass. You can see this in the plot, as data from Provider C and Provider D have a large spike in their densities at zero.

The tail of the distribution is varied. Some models, such as the one from Provider A, have a smooth and constant-looking distribution across high biomass values. This is compared to the outputs from Provider E, which show a fairly constant distribution but across low biomass values.

Detail and Structure

Resolution quality became very apparent when looking at features like hedgerows. Providers B and D offered higher-resolution outputs that, even when re-projected to a common 10m grid, clearly demarcated fields and picked up thin biomass features.

Despite differences in magnitude (how much biomass is there), the models generally agreed on where the biomass was. We used the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), a metric used in image analysis, to quantify this. We saw moderate scores (greater than 0.5) across most models, meaning they all agree on the "shape" of the forest, even if they disagree on the density.

The Uncertainty Factor

In my opinion, the most important feature of a model is its ability to admit when it is uncertain.

In financial markets, you demand to know the risk associated with a trade. We must demand the same from the monitoring that enables carbon credit transactions. Sophisticated buyers, like Isometric, are already using the lower bound of uncertainty estimates to determine credit sales. This effectively penalises uncertainty to ensure integrity. This is why we advocate for moving beyond generic global models for credit issuance. While a global model is great for screening, shrinking that uncertainty window (and unlocking the revenue trapped inside it) requires the site specific calibration (like drone/LiDAR fusion) found in integrated models like our Digital Twin.

However, making a direct comparison is difficult. The credible intervals provided aren't uniform across datasets—some use 68%, others 90%, and two models don’t provide uncertainty estimates at all.

When we compared the uncertainty bounds across the models, we found:

- Massive Range: The difference in uncertainty between models was as high as 150 Mg/ha in the most uncertain datasets. This is a huge range for a site-wide average. It is worth noting that the method of calculation matters here. Many approaches assume independence between pixels, whereas in reality, there are likely strong covariances between adjacent pixels (if one tree is there, another is likely nearby).

- Symmetry Issues: Not all processing steps were transparent, so we had to make assumptions. For three datasets, we derived bounds from the provided standard error. This creates symmetric bounds (mean ± error), which are likely incorrect because biomass is zero-bounded. You can't have negative trees. Note that the data from “Provider E” spans into negative biomass. A robust method to handle this is transforming the data (e.g., using a square root or a logarithm) to prohibit negative values in the probability distribution.

- Agreement in the Noise: Without extensive ground truth data, we can't definitively say which uncertainty bound is "right". However, for all providers that did provide uncertainty, they all fell partially within each other's 90% confidence intervals. This shows a degree of agreement despite the different modelling choices and data inputs (like terrestrial vs. airborne LiDAR).

- Heteroscedasticity: A fancy word for a simple concept: uncertainty changes over time. It was encouraging to see that for some datasets, uncertainty ranges were wider in the early 2000s and narrowed significantly in recent years as data quality improved.

The Power of Ensembles

So, if every model has different strengths and weaknesses, which one do you use?

The answer might be all of them.

By combining these outputs into an "ensemble", we can generate a consensus view. In the plot below, the dark green line represents the mean of the ensemble. This approach smooths out the noise and typically produces a more accurate estimate than any single model can achieve on its own.

The Takeaway

There are some impressive models out there, and it is encouraging to see the industry embracing remote sensing to monitor projects at scale. But for a non-technical project developer, purchasing data can feel like walking through a minefield.

Our intention with this analysis is not to criticise specific providers, but to highlight that trade-offs exist.

- Some models are better at detecting zero biomass (vital for baselines especially in ARR projects).

- Some are better at quantifying risk (vital for confident credit sales).

- Some models will likely perform better in certain ecoregions.

We hope the community continues to invest time in comparing models and standardising validation strategies. Transparency doesn't weaken the market. It gives it the robustness it requires and deserves.

For further reading on best practices, I highly recommend checking out Equitable Earth’s (formerly ERS) AGB benchmark methodology and the CEOS Working Group’s documentation on biomass product validation. Treeconomy will also be sharing some more investigations like this in the coming months.